A History of British Gardening Series – Victorian

In our History of British History Series – The Victorian period was celebrated for its progress, invention, new ideas and discoveries from giant glasshouses to garden tools.

| History of British Gardening Series |

|---|

| Roman |

| Medieval |

| Tudor and Stewart |

| Restoration |

| Georgian and Regency |

| Victorian |

| Edwardian |

| Modern |

Timeline

1840 The most popular plants for displays were chrysanthemums, dahlias and roses.

1840s James Pulham invents a cement that can be poured to form rockeries.

1841 Victorian gardener Joseph Paxton creates the glasshouse at Chatsworth. William Hooker starts his role as the new director at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Alexander Shanks of Arbroath registered a pony-pulled mower that cleared the clippings in 1841.

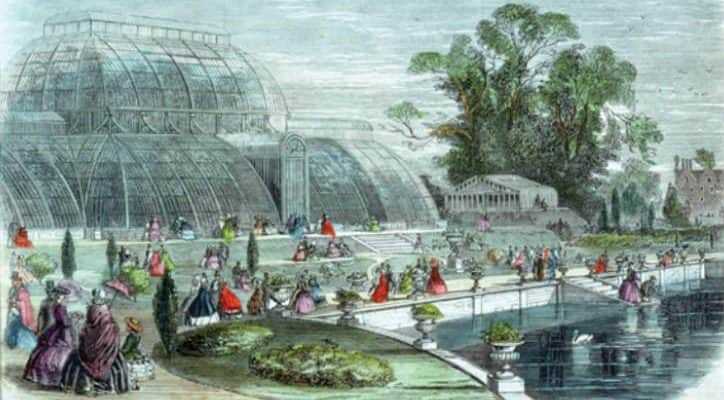

1844 to 1848 Architect Decimus Burton builds the Palm house at Kew.

1844 The monkey puzzle Araucaria araucana is reintroduced (after its first introduction in 1795).

1845 Glass tax is abolished, making greenhouses and conservatories cheaper and more popular. Conservatories, which made an attractive addition to the side of the house, were used for entertaining more than cultivating plants.

1847 James Hartley produces good quality sheet glass that’s used for greenhouses.

1848 to 1851 Joseph Hooker brings back 28 species of rhododendrons from his expeditions to the Himalayas.

1849 Joseph Paxton is credited with bringing the first the giant water lily into flower at Chatsworth House.

1851 The Great Exhibition of London takes place in Crystal Palace, designed by Joseph Paxton.

1854 Veitch Nurseries starts to sell seeds of Wellingtonia.

1859 Charles Darwin publishes the controversial On the Origin of Species by Natural Selection. Darwin also wrote regular articles for Gardeners’ Chronicles and devoted his later years to detailed studies of plants and the action of earthworms in the soil.

1860s Gnomes were introduced from Germany. Sir Charles Isham built a rockery in 1847 at Lamport Hall in Northamptonshire, which he filled with gnomes 20 years later. One still survives – who’s insured for £1m.

1861 The Horticultural Society becomes the Royal Horticultural Society.

1865 Joseph Hooker takes over from his father William Hooker as director of Kew.

1870 The Wild Garden by William Robinson promotes the idea of natural-looking planting schemes.

1874 The pesticide DDT is synthesised by Othmar Zeider. DDT is banned in 1972.

1887 The council introduces the Allotment Act. The council makes land available at a reasonable rent for the public to grow plants on.

1895 The National Trust is founded by Miss Octavia Hill, Sir Robert Hunter and Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley. The Trust was set up ‘to act as a guardian for the nation in the acquisition and protection of threatened coastline, countryside and buildings’. The first women gardeners are employed at The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

1897 The Victoria Medal of Honour in Horticulture, is established by the RHS. The medal is awarded to people who’ve made an important contribution to gardening, such as Alan Titchmarsh and Christopher Lloyd.

Victorian style of gardening

Gardening was no longer the exclusive hobby of the upper classes. As industry and commerce prospered, a wealthy middle class emerged who wished to live near their source of income but away from the squalor and overcrowding they had helped to create in the cities. Improved transport and roads made it possible for villas to be built on the outskirts of towns where there was fresh air and an opportunity to display new-found wealth.

There was a desire for gardens with ostentatious features, following the latest fashions and themes, rather than harmonising with the landscape. Communication speeded up with the arrival of the steam engine which epitomised the pace and energy of the time. The Victorian period was celebrated for its progress, invention, new ideas and discoveries. Edwin Budding’s new lawnmower invention meant that people could have manicured lawns, while gadgets such as cucumber straighteners were becoming increasingly popular.

When the Victorians weren’t inventing or constructing they were writing about developments in books and magazines so others could benefit. Better printing systems made it possible for more people to gain horticultural inspiration from the garden writers of the day, such as Loudon. The impact and spread of knowledge was greater and quicker than ever.

Wealthy Victorians also created public spaces. Loudon in the 1830s and 1840s was responsible for designing many public parks, encouraging the use of more broad-leaved trees and plants in place of evergreens. Intricate bedding schemes and patterns were popular. After the Allotment Act in 1887, space for growing plants became available at a reasonable rent to this rapidly expanding urban class.

Gardenesque (1832 to 1880s)

The Gardenesque movement started in December 1832 when John Claudius Loudon suggested a style of planting design in a magazine that moved away from the picturesque English Landscape movements and the obsession with natural form and movement.

It relied on using non-native plants and exotics, displaying them individually in beds so they were able to develop their true shape and could be admired from all angles. The garden designs were based on abstract shapes with specimen plants that were intended to look artificial.

Victorian characters

The plant hunters

Records of plant hunting date back to 1495BC when Queen Hatshetsup sent botanists out to Somalia to collect incense trees. But the Victorian period was the golden era of plant collecting. There was a desire for exploration and discovery and Victorian plant hunters were botanical adventurers who risked life and limb to bring back exotic plants from around the world.

Many of them died on their travels, but their legacy lives on in the plants that many of us now consider to be part of the quintessential British landscape.

William and Thomas Lobb

Cornish brothers William and Thomas Lobb were two of the most prominent and prolific Victorian plant hunters, working alongside the famous British plant nursery Veitch & Sons.

William introduced many species from North and South America, including famous plants such as the monkey puzzle tree and wellingtonia. Thomas travelled East and collected plants from Indonesia, India and the Philippines.

George Forrest (1873 to 1932)

George Forrest travelled mainly to China, Tibet and Burma. He was responsible for introducing about 600 species of plants, 300 of which were rhododendrons. He also brought back camellias, magnolias, Himalayan poppies and primulas.

Joseph Hooker (1817 to 1911)

Joseph Hooker, William Hooker’s son, brought back more than 28 new species of rhododendrons from his expeditions to the Himalaya in 1848 and 1851. The craze for rhododendrons soon swept the UK. Hooker was a close friend of Charles Darwin and eventually became director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

Robert Fortune (1812 to 1880)

Robert Fortune began his botanical career at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Edinburgh. He later became deputy superintendent of the Horticultural Society (later to become the Royal Horticultural Society) at Chiswick. In 1843 he was commissioned by the society to travel to China to collect plants. After travelling extensively through China and Japan, he introduced more than 120 species to English gardens.

Fortune’s overseas adventures included investigations into the commercial opportunities in growing tea. Commissioned by the British East India Company, he disguised himself as a Chinese peasant as he smuggled out cuttings of the tea plant Camellia sinensis from China into India. These cuttings enabled India and Ceylon to become established as major growers and exporters of tea.

Plants Robert Fortune introduced include: Trachycarpus fortunei, Dicentra spectabilis__Mahonia japonica, Jasminum nudiflorum and Skimmia japonica

William Andrew Nesfield (1793 to 1881)

William Nesfield was born in 1793. He graduated from Trinity College, Cambridge and enlisted in the army in 1809, fighting in Spain and Canada. He retired on half pay in 1816 and dedicated himself to painting watercolours between 1823 and 1843.

In the later half of his life, Nesfield’s passion changed to landscape gardening.

Drawing upon pre-18th-century garden styles, he gained a reputation for elaborate designs. His style often combined using elaborate parterres with modern plants.

He worked on Regent’s Park, St James’s Park, The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Grimston Park, Holkham Hall, Broughton Hall and Witley Court.

Sir Joseph Paxton (1803 to 1865)

Paxton was probably the most famous of the Victorian gardeners. The son of a farmer with only a very basic education, Paxton eventually became responsible for the gardens at Chatsworth House owned by the Duke of Devonshire.

Paxton designed the new conservatory at Chatsworth which was built to a distinctive ridge and furrow pattern and later the Crystal Palace in London, for which he was knighted by Queen Victoria. He eventually became a millionaire because of commercial investments, such as selling small greenhouses to amateur gardeners.

John Claudius Loudon (1783 to 1843)

John Loudon was a major influence on gardens and gardening during his lifetime. One of the key gardens he designed – Birmingham Botanic Gardens – became synonymous with the Gardenesque movement.

A prolific writer, it’s estimated that Loudon wrote more than 66 million words in his lifetime. In The Gardener’s Magazine he enthused and educated the newly prosperous middle classes with gardening tips and advice.

Loudon was a great campaigner and fought hard for better pay and conditions for gardeners. He also came up with the idea for a green belt around cities which he called ‘breathing zones’. His efforts transformed middle class gardens around Britain.

Victorian themes

Ferns

Fern collections became extremely popular. Victorians kept them in specially designed glasshouses known as ferneries.

Fruit

Growing exotic fruit such as figs and dessert grapes in greenhouses became popular. So did training hardy fruit trees in styles like espalier, cordons and fans, which would adorn the sides of walled gardens.

Arboretums

Woodland gardens were a very popular way to display the new rhododendrons and azaleas from China. The discovery of ornamental trees from abroad prompted wealthy landowners to enhance properties with an arboretum.

Terraces

Formal gardens were back in fashion, especially the classical style. An Italianate terrace was considered a suitable platform for both a noble and a middle-class house, an architectural device that linked the garden to the house. These terraces were usually balustraded and decorated with urns, vases, grandiose flights of steps and parterres.

Bedding displays

Low box hedging would surround flowerbeds filled with bright contrasting bedding plants. Tender or half-hardy varieties, such as geraniums and lobelia, were varied from year to year or season to season. These gaudy displays were an ideal vehicle to show off the owner’s financial wellbeing and their gardener’s talents.

Bedding plants organised in intricate patterns became fashionable in both private gardens and public parks in the 1830s, as tender flowering plants began to arrive from places such as South Africa and Mexico. Plants including pelargoniums, heliotropes, salvias, lobelias and cannas were used to add bright splashes of colour.

Roses

Roses, chrysanthemums and dahlias were going through a rapid evolution via hybridisation. By 1840 there were more than 500 cultivars of dahlias. In Victorian times the fashion was to have a separate formal rose garden within the boundaries of the main garden.

Then, at the beginning of the 20th century, designer Gertrude Jekyll led the way to a more relaxed method of using roses, pioneering the use of mixed borders, climbers and ramblers.

The Monkey Puzzle tree

The monkey puzzle became the ‘must have’ plant of Victorian society. It would be planted to be viewed as part of the landscape or, in smaller, suburban gardens, as the central feature to a bedding scheme.

It was introduced to Britain in 1795 by Archibald Menzies after his visit to Chile. But the plant remained a rarity until the 1840s when William Lobb rediscovered the tree on a plant-finding mission to South America. He sent the seeds back to Veitch Nurseries who’d funded his trip.

By 1843 Veitch Nurseries was offering 100 seeds for £10.

Wellingtonia trees

The Victorians loved the giant Wellingtonia trees because of their impressive size. They were planted in many gardens as specimen trees, and in rows creating Wellingtonia avenues.

Introduced by the plant hunter William Lobb in about 1854, the naming of the tree caused an international row between Britain and America. In Britain the tree was named Wellingtonia gigantea after the Duke of Wellington, who died in 1852. Yet the Americans wanted to call it Washingtonia, after the first US president George Washington.

After years of dispute, it was finally named Sequoiadendron giganteum because of its similarity to the Californian redwood (Sequoia sempervirens).

The original content was published on the BBC Gardening website, however the Design section with all of its content has been removed. We try to keep this great content alive here on the Gardenlife Pro site.